Serious concerns about the impacts we have on the planet have been around for a long time. By the late 18th Century as the world adapted to the Industrial revolution, an English cleric addressed the problem in a small book and added his name to the English language. An Essay on the Principle of Population by Thomas Malthus was published in 1798 and influenced the thinking of the world’s first economists as well as that of Charles Darwin and compelled the British government to take regular censuses of the population to shape its planning.

The central paradox set out in the book suggests that when population increases geometrically (by multiplication), and food production grows arithmetically (by addition), the ultimate result can only be depressed wages, increased prices and then starvation. The word Malthusian entered the lexicon to describe this paradox.

What we now know is that Malthus had ignored a third variable in his thinking. He had overlooked human ingenuity and its impact and so assumed the future would be an extrapolation of the present, not the taking of another path. Over two hundred years later, we worry less about having enough to eat than about obesity and food waste.

A new equation

A similar debate can also be discerned in the way in which the commercial property market responds to the changing needs of organisations. In the past, it has been possible to directly correlate the number of people employed with the amount and type of space an organisation needs to provide them with an office. Both have traditionally grown arithmetically in parallel. This linear thinking is codified to some extent in guidance from the British Council for Offices and the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors.

In a recent piece from Richard Kauntze, CEO of the BCO published in the Architects Journal the average space allocated to a British office worker is currently around 9.6 sq. m. per person (and falling) which Mr Kauntze compares unfavourably to the space given to their Danish counterparts.

Yet, as with Malthus’s theory, the equation is now complicated by other variables, not least the changing ways we use office space and think about the places and times we work. The present and future of the office are arrived at by new paths rather than those that have been trodden before.

The past few years have seen profound changes in the way organisations design and manage their offices and the relatively simple equation of space efficiency has been supplanted by something more sophisticated. Once, office design and management focussed on Taylorist notions of churn, space efficiency and the need to express hierarchy through the size of dedicated workstations and ownership of private rooms. Leases were long, time and place were relatively fixed. Now it is defined by democratic design principles with space shared between people from different disciplines, as is the case with the new Sedus Smart Office. At the same time, the property market is being reshaped by the forces of coworking.

Such changes are not merely an evolution of what has come before but the creation of new forms of workplace. The future of the office will be shaped by new forces, new technology and new ideas.

Smart tech. Smart offices.

None of this means that the traditional headquarters office will disappear. In fact, it could be argued that its importance is actually increasing. The world’s leading creative and technology firms are committing to new offices on an unprecedented scale as a way of bringing people together to have better ideas and develop stronger relationships with each other and their employer.

What is interesting is the form these new buildings take, borrowing not only the language of other forms of building, but their aesthetic and functional characteristics to forge a new experience for the people who inhabit them. Specific spaces for different types of work and different organisation structures and lines of communication become available on demand just as they are for eating, drinking, socialising and relaxation.

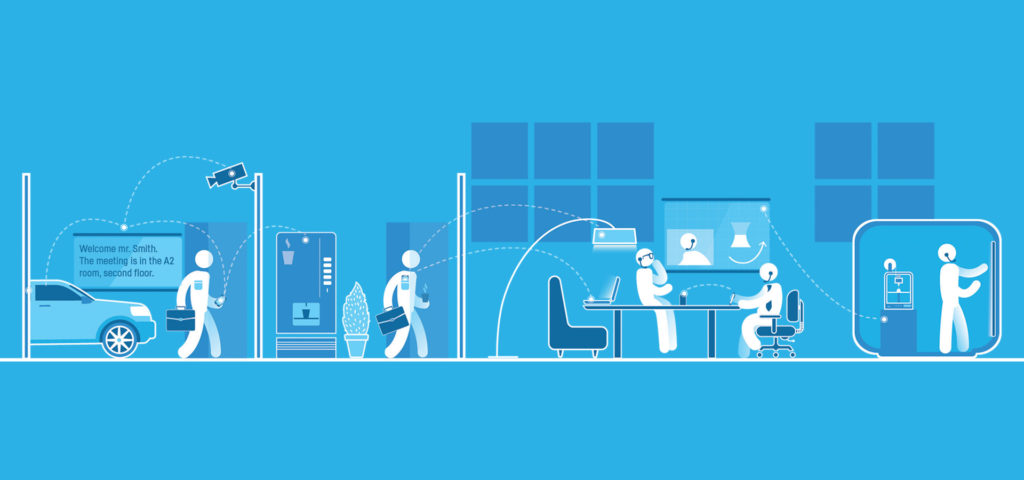

Embedded smart technology allows people to see which spaces are available that most meet their needs and feeds data back to the organisation so that it can adapt the workplace over time to more closely align with the needs of its users.

This convergence of the digital and physical workplace is the subject of the latest issue of Sedus Insights To Efficiency and Beyond which looks at the implications for office design and the way we inhabit and manage offices in this part of the 21st Century.